Silenus and his Mask

Slow going is the proper term to describe this new project. I’m trying to investigate the reception of Plato’s Symposium in the ancient world [[1]]. This is already a challenge, since there is very little information concerning commentaries and adaptations of Plato’s Symposium in the philosophical tradition: Calvenus Taurus (T 5 Lakmann) complained that the lazy budding philosophers of his day only wanted to hear about Alcibiades’ revelry; Plutarch might have written his own version of the Symposium, which would have focused on, among other things, obtaining a definition of love (e.g. F 135 Sandbach); Porphyry appears to have written a commentary on it, of which one testimonium survives (177 T Smith). But very little by way of philosophical commentary on Plato’s justly celebrated work is extant, or even hinted at, in the ancient world.

On the other hand, so-called ‘literary’ receptions of the Symposium are somewhat plentiful: witness, for example, Lucian’s Symposium, also known as the Lapiths, which begins by exploiting Alcibiades’ late entrance:

Philo: All sorts of tomfoolery, so they say, happened yesterday to you guys at the dinner party at Aristaenetus’ house: some philosophical speeches were made, thanks to which a quite substantial quarrel arose. Unless Charinus was lying, it all came to blows, and the party was broken up by bloodshed.

Lycinus: Where did Charinus get hold of this information, Philo? He didn’t eat with us!

Philo: He said he heard it from Dionicus, the doctor. I suspect that Dionicus was one of the guests.

Lycinus: True enough; but he wasn’t even there for all of it from the beginning: he came in quite late, when the battle was half over, right before it came to blows. So I’d be surprised if he could say anything specific about it, since he wasn’t there for the beginning of the quarrel which ended in bloodshed.

(Lucian, Symposium or The Lapiths 1)

Obviously, Lucian is exploiting the trope of distancing the account through establishment of narrative registers found at the beginning of Plato’s Symposium (172b-174a); but he innovates by making Dionicus arrive late, like Alcibiades, and casting him as a doctor, like Eryximachus. Moreover, at the end of the story, after the dispersal of the dinner party, he stands in for Socrates too, who tucks in his friends before leaving for the Lyceum (223d):

Lycinus: The bridegroom, after his wound had been dressed by the doctor Dionicus, was carried home, head bandaged, in the carriage in which he was planning to carry his bride – bitter was the wedding he celebrated! As for the rest, well, Dionicus treated them to the best of his ability and they were carried off to bed, most of them puking in the streets.

Sounds like a Thursday night in Newcastle! At any rate, it is somewhat striking to see Dionicus take on so many masks here: the person who told Phoenix the story of Agathon’s party, Eryximachus, Alcibiades, and finally Socrates. Maybe that’s part of the reason why Lycinus quotes the famous closing lines of several plays of Euripides (Alcestis, Andromache, Bacchae, Helen, and Medea) at the end of Lucian’s work (Symposium 48):

Many are the shapes of divine things,

And many are the things the gods bring to pass unexpectedly,

As things expected were not brought to completion.

πολλαὶ μορφαὶ τῶν δαιμονίων

πολλὰ δ’ἀέλπτως κραίνουσι θεοί,

καὶ τὰ δοκηθέντ’ οὐκ ἐτελέσθη.

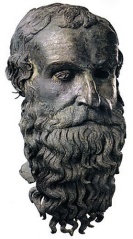

Like Proteus, or a mime performer, Dionicus combines many of the shapes of those heroic figures of the Symposium‘s literary past into one character, a kind of syncretism that – in itself – counterbalances the squabbling and outright brutal warfare demonstrated by the philosophers whom he was left to tend to at the end of the work. Like the Silenic Socrates who, according to Alcibiades (215b; cf. 217a), is full of “statuettes of the gods” (ἔνδοθεν ἀγάλματα ἔχοντες θεῶν) – and whose speech adapts and comes to contain all the others that come before – Dionicus embodies many of characters who participated in the paradigmatic Platonic Symposium. Lucian’s is a unique (I think) model of intertextual syncretism in the ancient literary tradition that reinterprets Plato’s masterpiece of literary and philosophical composition on its own terms. But perhaps I’m wrong, and people can point me to other texts?

[[1]] It is worth citing, among others, Richard Hunter’s Plato’s Symposium (Oxford, 2006) as well as Harold Tarrant’s Plato’s First Interpreters (London, 2000) as major studies that deal with the reception of Plato’s Symposium.